What’s better than youth taking part in Seeds of Peace dialogue? When Seeds use their facilitation skills to create opportunities for more youth in their communities to do the same.

Not long after attending Seeds of Peace Camp in Maine, Samir, a 2019 Pakistan Seed, conceived the idea of a program that would allow opportunities for more youth to get a taste of the transformative power of dialogue that he had experienced.

“I honestly felt enlightened after my dialogue and felt that I had the power to change the world,” Samir said. “I still carry that power, and I am not ready to let go of it. I will pick myself up if I fall down, because if not me, then who’s gonna bring the change?”

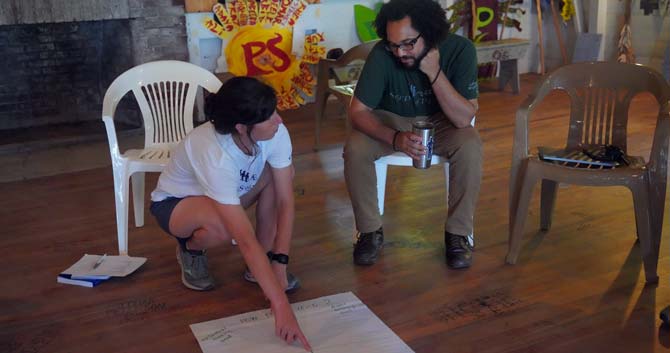

Earlier this summer, with the support of 2018 Seed Ali Haris and the Wonder Y Academy (which Ali founded), Samir organized and hosted “Dialogue for Changemakers,” a six-day dialogue program for teenagers.

The in-person program took place at Titan College in Karachi and was completely student-run, including with several volunteers who participated in the Seeds of Peace 2021 Pakistani Youth Leadership and Dialogue Camp. Thirteen students (selected from a pool of 50 applicants) explored complex topics like religion, culture, nationality, and gender within Pakistani society while learning the fundamentals of dialogue in a supportive environment.

“You bond in a different way with your dialogue group because you speak your heart out without the fear of being judged,” Samir said. “That kind of comfort is not available for people

out there. So, I wanted this space to be a safe space for them and the people to be there for each other as support systems so they can hold each other in the tough times we find ourselves shackled in.”

It is especially during these challenging times, Samir said, that it is most important for youth to hear opposing viewpoints and learn from one another.

“Dialogue is an alien term to many Pakistanis,” said Hana Tariq, head of curriculum for Beyond the Classroom, which partners with Seeds of Peace to run local programs in Pakistan. “Seeing Seeds like Samir creating safe spaces for dialogue in the most meaningful way possible, is the change we wish and hope to see.”