NEW YORK | Over 270 supporters, friends, and alumni of Seeds of Peace gathered in New York City on May 27 to honor the past, present, and future of the organization while helping raise over $1.1M for the organization’s mission.

The 2025 Spring Benefit Dinner, hosted by MSNBC’s Ali Velshi, was filled with music, reflection, and purpose—honoring the transformative power of dialogue, the legacy of leadership, and the resilience of a global community committed to peace.

“Tonight is something rare,” said Velshi. “Different backgrounds, different politics—but united by a shared hope and by Seeds of Peace’s invitation to imagine and build a different future.”

The evening honored Seeds of Peace’s programming team around the world, from South Asia to the the Middle East to the United States, who have, in the face of unimaginable challenges, remained steadfast in their mission.

Seeds representing different eras of the organization’s history, from 1994-2024, shared deeply personal testimonies about how their Seeds of Peace experiences have shaped their lives and inspired their work as changemakers in their communities.

The room was brought to its feet by stirring performances from Anuradha “Juju” Palakurthi, accompanied by rapper Xenai and composer Ishaan Chhabra. Their music, rooted in Indian culture, embodied the spirit of courage and connection. Equally moving was the performance by the internationally acclaimed Palestinian-Israeli Jerusalem Youth Chorus, founded by American Seed Micah Hendler.

“This evening is about the believers and doers,” said Seeds of Peace Executive Director Eva Armour.

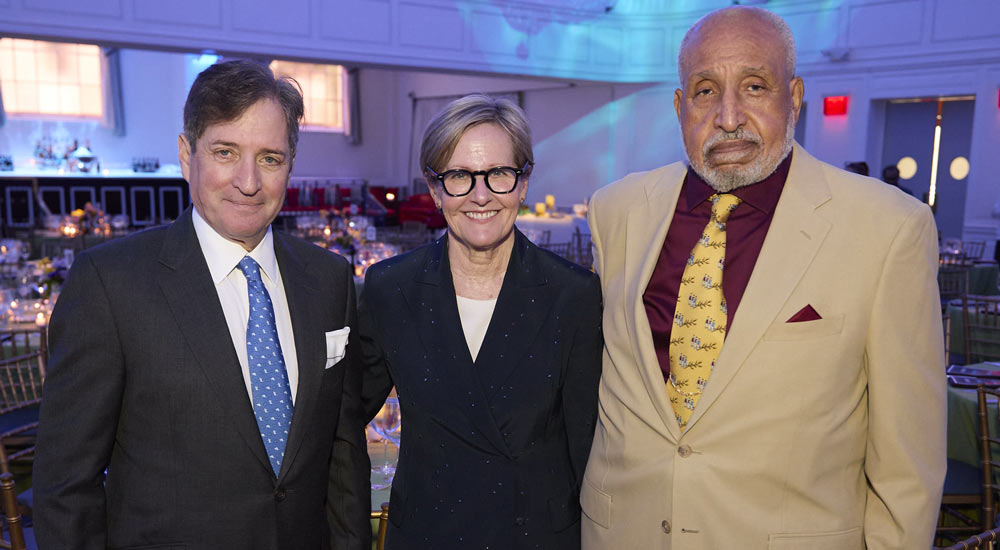

Seeds of Peace Board Chair Sandra Wijnberg received the John P. Wallach Peacemaker Award in recognition of her commitment to fostering understanding and peacebuilding, including her work with the Office of the Quartet in Jerusalem promoting economic development to advance Middle East peace.

“This organization has proven its resiliency over 30 years—through times of great hope and great despair,” said Sandra. “Tonight is a tribute to everyone who believes as [Seeds of Peace founder] John Wallach did in the importance of investing in the next generation.”

The event also celebrated a tireless advocate for youth diplomacy and dialogue, the Honorable Jay T. Snyder, who was introduced in a video message from Bill and Hillary Clinton, as well as Timothy (Tim) P. Wilson, the longtime Seeds of Peace Camp Director whose leadership has shaped generations of young peacebuilders.

This evening was more than a celebration: it was a renewal of our shared commitment to a more just and peaceful future with those who continue to invest in the work of Seeds of Peace.